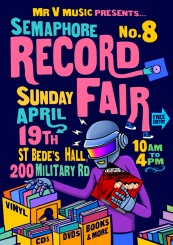

Record Store Day at the Semaphore Record Fair – 19 April 2015

Punters flocked to Semaphore for the Record Fair on 19 April. Whilst the advertised starting time was 10:00 am, business was brisk from 9:00 am and St Bede’s Hall was crowded throughout. The weather was cool outside the hall but inside trading was hot. And so were the pies prepared by the local church support group.

At White Elephant Records we recorded good sales generally including a mint condition John Lennon Yoko Ono album – Two Virgins and a mint condition Live Box Set of Bruce Springsteen, which sold in the eighties by the million.

There were some interesting new albums on offer and some older gems to be picked up, including Ryan Adams’ latest self-titled album, an oddity from Eric Clapton, titled Old Sock, Marianne Faithfull’s latest – Give my love to London, and a reissue of Rory Gallagher’s epic Calling Card.

The older gems were harder to come by but a few cropped up including young instrumentalists Santo & Johnny – Come On In, Count Basie – a CBS special jazz issue – The Essential Count Basie Vol 3, Yehudi Menuhin, Ravi Shankar and Jean Pierre Rampal – Improvisations West Meets East – Album 3, a German issue Rory Gallagher – Pop History Vol 30, and a Kingston Trio double live album – Once upon a Time, which has an interesting history and a Review by Bruce Elder on AllMusic is appended below:

“In July of 1966, the Kingston Trio began a three-week engagement at the Sahara Tahoe Hotel in Lake Tahoe. The trio and their manager considered it the beginning of their final 12 months as an active group, and had the tape recorders running — the idea was that upon the announcement of their farewell tour, a double-LP live set would be in the can and ready to be released. But as it turned out, neither their current label, Decca Records, nor their prior label, Capitol Records — which had issued three complete concert albums by the group — was interested in issuing the farewell album. Instead, the record remained on the shelf until 1969, when Bill Cosby’s Tetragrammaton Records issued Once Upon a Time; amazingly, the album made it into the lower regions of the Top 200 albums for six weeks (which leads one to suspect that Bob Shane had been correct in his commercial instincts, in his resistance to breaking up the trio in 1967). Tetragrammaton folded in the early ’70s, and the resulting double LP is one of the rarest in the Kingston’s Trio’s output, which is sad — the best of their concert recordings since those renowned live recordings of 1958, it captured the group ranging freely across its history and the folk landscape, including two songs associated variously with the Weavers and Leadbelly (“Wimoweh” and “Goodnight Irene”), a trio of Bob Dylan songs (“One Too Many Mornings,” “Mama, You Been on My Mind,” and “Tomorrow Is a Long Time”), and a Donovan song (“Colours”), and travelling back through their own history (“Tom Dooley,” etc.) and giving their best Decca single (“I’m Going Home”) a fresh airing. If there is a flaw here — apart from the momentary appearance of the Sahara Tahoe Hotel orchestra on the introduction sequences on each platter — it is the result of a desire not to repeat too much material off of the group’s earlier concert albums, so that some songs, such as “Pullin’ Away,” are not present here. In compensation, listeners get a real live version of “Where Have All the Flowers Gone,” which was represented on the College Concert album by a studio version with dubbed-on applause; their best piece of released topical humor, “Getaway John”; and “Ballad of the Shape of Things.” The latter leads into the best version of “Greenback Dollar” ever issued by the threesome in any incarnation, and they’re able to slide from that into a nicely wry intro to “Mama, You Been on My Mind” (as “Babe, You Been on My Mind”) — actually, their versions of Dylan songs here are a major breakthrough for a group that kept his music at arm’s length (or further) for years, and show just how much further the trio could have gotten. In any case, the resulting 72-minute album runs circles around their last live album for Capitol (Back In Town), as well as most of their late Capitol work and a lot of their Decca sides, and it’s worth tracking down.”

What a review. So you should always expect the unexpected at Record Fairs. Work your way slowly through the racks and boxes and stacks of albums. With a little dedicated search and rescue there is often a rich reward awaiting.

Bookselling was also well represented at the Fair. Harry B, as usual, held sway on the hall’s bandstand with a several tables of music books. He was complemented by the “comic book” people who had a swag of music books at microscopic prices, and also Quenton L at the entrance of the hall near the servery. Proud acquisitions include:

Robert Shelton’s updated bio of Bob Dylan – No Direction Home (The Life & Music of Bob Dylan) (2011) , a story about the vinyl record – Travis Elborough’s The long-Player Goodbye (2008), The British Invasion by Nicholas Schaffner (1983), Tomorrow is Today (Australia in the Psychedelic Era 1966-1970) – ed Iain McIntyre (2006), and the mesmerising Bodgie Dada & the Cult of Cool – John Clare/Gail Brennan (1995).

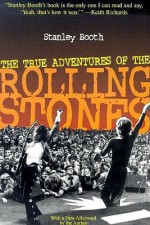

And one of the great buys was Stanley Booth’s – The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones (1986), which was reprinted in 1989, 1990, 1992, and 1994 (twice), and a revised version released in 2012. The latest version of the book was reviewed in The Guardian newspaper in April 2012 with a great report by Richard Williams (Courtesy The Guardian).

“The small man with carefully brushed long hair and tinted glasses sat quietly as the band played a competent version of “Little Red Rooster”. He and a friend, into whose ear he occasionally directed a comment, were among the few occupants of a small area of the room roped off for VIPs. On this night in March 2012, the 75-year-old Bill Wyman was the guest of honour at an event to celebrate the golden jubilee of the Crawdaddy Club, where his former group, the Rolling Stones, played their first residency.

It had all begun at the Station Hotel, Richmond, an unknown group in front of an audience that started in single figures but grew so quickly that within weeks the landlords began to fret about rowdiness and pulled the plug. The musicians decamped to the nearby Richmond Athletic Club, where trad bands had previously held sway, and spent several months establishing themselves as the first among equals of the new wave of rhythm and blues groups arising from the rich alluvium of the Thames Delta: the Yardbirds, the Downliners Sect, the Pretty Things.

This was where Wyman was sitting last month, under the same low ceiling, with fellow celebrants leaning against a bar decorated – then as now – with rugby club memorabilia. He was listening to a musician a couple of decades younger than himself, a man with long grey hair scraped back in a ponytail, stroking out the bottleneck guitar phrases once played by Brian Jones on the song – borrowed from the repertoire of the blues singer Howling Wolf – that, after the Stones had played it on Ready Steady Go!, became their first No 1 hit.

“At Richmond we became a sort of cult in a way,” Charlie Watts told Stanley Booth, the author of The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones. “When the last encore would die down, you were nearly dead with sweat, you can’t do more than four hours, and they had to shut the place up.” Keith Richards put it more succinctly. “This,” he told Booth, “was where we stabbed Dixieland jazz to death.”

The Stones were sniffing the scent of real success as rivals to the Beatles when they played the Athletic Club – where there was no stage, so they had to set up their instruments on the same level as the audience, who could dance within inches of the musicians – for the last time in November 1963. The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones, first published in 1984, carefully pieces together the story of the group’s swift rise, but its real purpose is to describe, from an unusually intimate perspective, the existence of the group at the end of the Sixties, when they were at the height of their power and notoriety.

By far the best work on its subject (including Richards’s own well received effort), Booth’s book is also easily the most convincing account of life inside the monster created by the rock revolution of the 1960s. The author, a Georgia boy who had vowed at the age of 15 “to become a writer or die trying”, was fiddling about with journalism as a prelude to a literary career when he secured a trip to England to write a magazine piece about the Stones in 1968, meeting the group briefly and covering Jones’s trial for possession of drugs.

“I wrote a story,” he recalled, “but I had only glimpsed – in Brian’s eyes as he glanced up from the dock – the mystery of the Rolling Stones.” A year later, with a contract to explore the mystery further and turn his article into a book, he joined them on the tour that would end at Altamont the free festival at which the hopes and dreams of the hippie era came to a bloody end.

The Stones took to Booth right away: he looked and dressed like them, he spoke with the genuine Southern accent that Jagger could only counterfeit, and he took all manner of drugs with them. He had lived in Memphis, and his understanding of the music that had inspired them was first-hand, unlike that of the swottish English blues fans who could only wait for records to come from America, using them as the measure by which to pronounce judgement upon the Stones’ musical authenticity. “I had managed,” he writes, establishing his bona fides, “to sweep the streets with Furry Lewis, throw up at Elvis presley’s ranch (overdosed on the painkiller Darvon by Dewey Phillips, the first man to play an Elvis record on the radio), drink Scotch for breakfast with BB King, watch Otis Redding teach Steve Cropper ‘The Dock of the Bay’ and now I was raiding the country with the Rolling Stones.”

Carried along by the tide of the tour, he is too cool to ask the kind of questions with which the band are confronted by the straight media (the celebrated gossip columnist Rona Barrett, at a press conference in Hollywood: “Do you consider yourself an anti-establishment group, or are you just putting us on?”). They and their entourage open up to him; Anita Pallengerg, for example, explains the real reason why Jones was missing recording sessions and concerts, allegedly because he had injured his hand in a fall. “Anita told me that Brian had broken his hand on her face, during a fight. ‘He always hurt himself,’ she said. ‘He was very fragile, and if he ever tried to hurt me he always wound up hurting himself.'”

Jones is dead, drowned in his own swimming pool, by the time Booth hooks up with the band in America. Now the author’s notebooks started to fill up as joints are smoked on private jets under the eyes of New York police officers hired as security men, cocaine is hoovered up from film canisters, heroin lurks in the background and a fan hands Watts a yellow-green LSD tab. “Charlie asked, ‘D’you want it?’ ‘I ain’t too sure about this street acid,’ I said. ‘Maybe Keith will want it.'” In San Diego, Booth listens as Jagger experiences an important moment of revelation: “‘All these kids are so stoned.’ It was true, the Stones were for the first time playing to kids who were under the influence of dope.”

They are in northern California when Booth notes: “In the early days the Stones could and did handle a riot every night, night after night, kept going, taking no dope of any kind. ‘You couldn’t,’ Keith said. ‘You couldn’t keep going if you did, not even booze, no pills, nothing.’ But in 1969 things had changed. It would be impossible to endure a world that makes you work and suffer, impossible to endure history, if it weren’t for the fleeting moments of ecstasy. As you get older, it’s harder to cook up the energy, even if your life is composed of distant beaches, soft female skin, plane rides, cold concrete arenas, cops, fatigue, cocaine, heroin, morphine, marijuana, busted amplifiers, riots. You have to get it from somewhere, which is why Jagger said, ‘All right, San Francisco, get up and shake your asses.'”

Returning from a concert in Europe the previous year, Jagger had spoken of an increasingly hysterical edge to the communion between the musicians and their fans: “When I’m on stage, I sense that the teenagers are trying to communicate to me, like by telepathy, a message of some urgency. Not about me or about our music, but about the world and the way they live. And I see a lot of trouble coming in the dawn.”

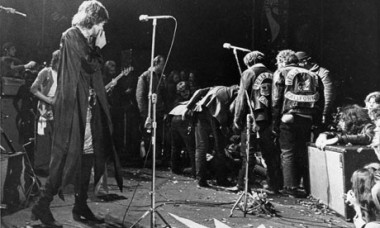

That trouble arrives in the hours before dawn at Altamont Speedway, where several hundred thousand kids gather for a free festival destined to end in mayhem and the murder of a young black man, stabbed and kicked to death by members of the Hells Angels who had been unwisely invited to police the stage. Booth’s account, assembled from the evidence of his own eyes and those of other tour members, is a descent into the inferno, with a bizarrely poignant moment when Jagger, attempting to calm things down, summons the memory of afternoons by the wireless during his Dartford childhood and asks: “Now, boys and girls, are you sitting comfortably?”

As the Angels’ dying victim is carried away and thoughts turn to evacuating the group from the crime scene to their waiting helicopter through a landscape that will become familiar from movies set in post-apocalyptic worlds, Booth clings to his vantage point behind the amplifiers, listens to his travelling companions pound “Street Fighting Man” to a conclusion, and glimpses a truth that will evade subsequent generations doomed to see the Rolling Stones only in vast modern stadiums, acting out their latter-day role as the biggest and best heritage act of all. “No one,” he writes, “could say that the Rolling Stones couldn’t play like the devil when the chips were down.” (Courtesy The Guardian Saturday 7 April 2012 Richard Williams)

All in all the Semaphore Record Store Day Fair was very good from both a selling and buyers’ perspective. Now we are looking forward to the big one – MusicPalooza in July – but Semaphore just keeps getting better.

And another big thank you to Vic Fleurl for arranging Semaphore and may Mr V Records forever prosper.

Leave a Reply